News

Intercultural mediation: how to guarantee rights and access to services for Third Country Nationals

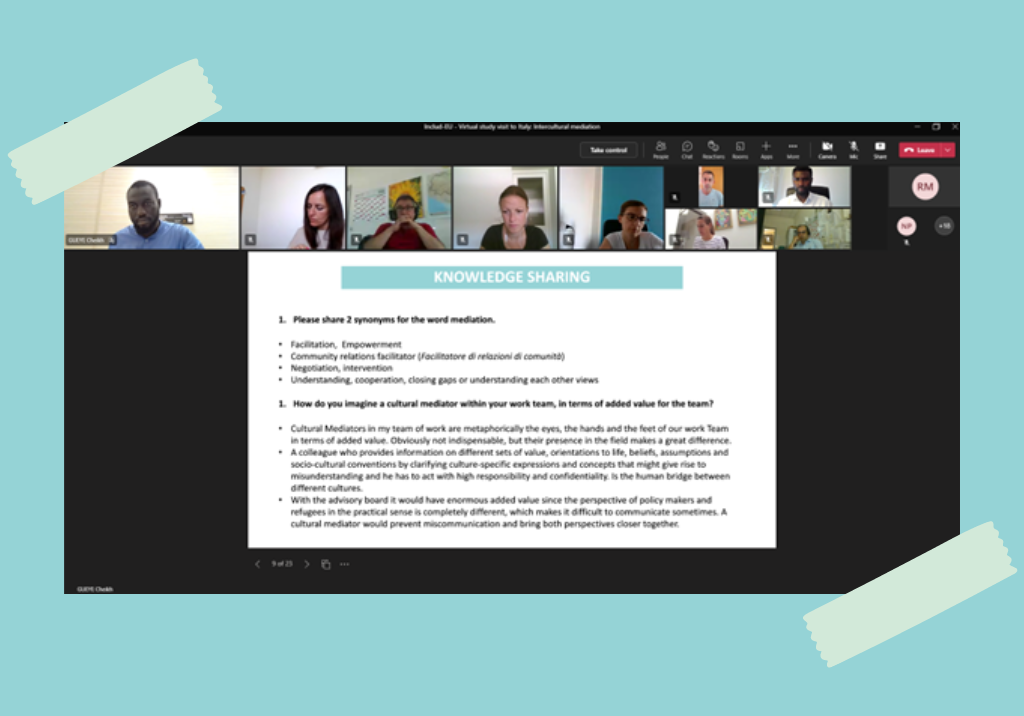

Exchange with Italy

Intercultural mediation is a newly emerging profession in Europe, although the practices of dispute resolution, conflict prevention and translation are as old as the first migrant flows to Europe. It has been gaining attention in parallel to the increasing focus on social cohesion policies in migrant-receiving societies.

Indeed, intercultural mediation plays a decisive role in the process of Third Country Nationals’ (TCNs) integration into the host societies and the number of initiatives with the key role of this profession are multiplying. Unfortunately, this doesn’t correspond to the institutionalization of this job’s mandate, study background and support provided throughout the undertaking of the tasks envisaged.

In light of this, the Includ-EU Team in Italy designed a programme which tried to give some examples of positive initiatives on intercultural mediation as well as tools to support the work of intercultural mediators (IMs).

Focus of the exchange

The programme of the virtual exchange focused on the Italian framework regarding intercultural mediation and the different initiatives that IOM has been implementing with the support of these key professionals.

Starting with the United Nations General Assembly’s Uniform Mediation Act in 2002 and the introduction of the European Code of Conduct for Mediators in 2004, intercultural mediation for supporting migrants’ integration in Europe has become more visible. Each European country nevertheless has its own legislative framework in the sphere of mediation, resulting in lack of harmonization and shared standards of intercultural mediation in a number of Member States, despite European Union (EU) directives to regulate and systematize the work of mediators.

Intercultural mediation plays a decisive role in the process of TCNs’ integration into the host societies: despite Italy recognizes this, an organic legislation that defines the profession of the intercultural mediator has never been adopted at the national level; nevertheless, there are numerous references to mediation activities in the legislation on immigration and integration of foreign citizens.

The qualification of Mediator is also well defined in the official professions classification; in addition, Italian Regions have adopted numerous regulatory measures to regulate the recognition of this figure, its areas of activity and the training path that allows access to the qualification of intercultural mediator.

Good practices

As previously mentioned, to date, there is no officially recognized, centrally regulated training for intercultural mediation at national level. Training for mediators is provided mainly by civil society organizations, universities and local public authorities, and includes both theoretical and practical components of mediation.

While Italy’s intercultural mediation training is comprehensive although not centralised, it could be improved by the introduction of an intersectional lens to mediation and its beneficiaries. As migrants’ needs depend on their intersectional identities and experiences, mediation practices should respond to those different needs.

Cultural mediators open a channel of communication with migrants, a task that requires linguistic competencies and a thorough knowledge of the migrants’ culture, the interiorised social norms and behavioural codes and communication and active listening skills, which create a relationship of trust. Such trust is a pre-condition to identify migrants’ needs and the appropriate assistance required. Moreover, a sound knowledge of the local context allows the linguistic and cultural mediator to communicate the information in a manner that makes it easier for the migrant to understand the situation and surrounding context, which may appear unfamiliar and confusing.

Lessons learned and future challenges

Several inspirational thoughts and lessons learned came out from the discussion, starting with the selection of intercultural mediators, who shouldn’t be only chosen for their nationalities: instead, there is a strong need to focus on their capacities of mediation, facilitation and creation of connections. In addition, this is also food for thoughts on the “issue of nationality”, taken also into consideration the so-called new generations and people with migratory background. Moreover, cultural mediation doesn’t entail only attention to verbal and/or linguistic aspects: emotions are fundamental and need to be interpreted differently and according to one’s culture; the same shall be applied to the understanding of different terms and what these words and acts mean to others.

All these tasks and approaches shall be integrated in the definition of actions and interventions, so as to make them more migrant-centered. At the same time, however, cultural mediators should be a “tool” of awareness raising who don’t substitute migrants but actually support their empowerment. They build trust, demystify stereotypes and bridge the gap between local and migrant communities; to enable them to do so at the best possible level, they should also be supported in enhancing diversity management skills: this path will produce positive effects on the final beneficiaries of the action they support, and also the indirect ones, meaning the actors/institutions they closely work with.

These positive effects are possible when intercultural mediators are provided with constant training and support, which are tailored to real contexts and contents; a code of conduct of the profession could be useful for this purpose. These tools need to be regularly updated so as to address new challenges and include lessons learned.

Do you want to share your project with our community and stakeholders?